Is Sugar That Bad?

A deep dive into recent data

During the 1970s, there was a growing consensus in the medical community that saturated fat was a primary contributor to heart disease, leading to a surge in low-fat food products. However, these low-fat products often contained high levels of sugar as a taste enhancer, inadvertently leading to increased sugar consumption.

John Yudkin, a British physiologist and nutritionist, was one of the early critics of sugar consumption. In the 1970s, he published a book titled "Pure, White, and Deadly," arguing that sugar, rather than fat, was a more significant threat to health, particularly in relation to heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

The original title of the book by Yudkin was sweet and dangerous.

His work pointed out that sugar consumption led to increased levels of triglycerides, a risk factor for heart disease, and heightened insulin levels, linking it to type 2 diabetes. Despite his findings, Yudkin faced significant opposition from the food industry and some scientific peers, leading to his marginalization in the scientific community.

In recent years, however, there has been a growing body of evidence supporting Yudkin's early assertions about the health risks associated with sugar. Research has highlighted the role of sugar, especially fructose, in metabolic disorders, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases. The sugar industry has been accused of influencing scientific research to downplay the harmful effects of sugar, similar to tactics used by the tobacco industry. For instance, in the 1960s, the Sugar Research Foundation paid scientists to minimize the link between sugar and heart health while emphasizing fat as the main cause of heart disease.

Lately, there's been a noticeable shift in the conversation around sugar, with a growing chorus in health and nutrition podcasts branding it as the root of all evils in disease.

This kind of echo chamber effect always gets my skeptic senses tingling. I decided to dive into the data headfirst to see what's really up and I'm here to share the findings with you.

What is sugar?

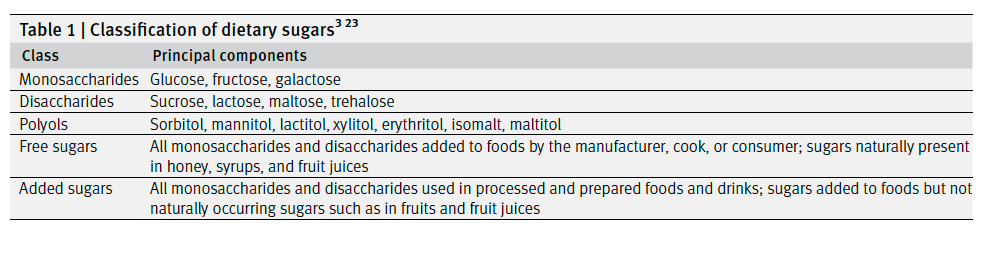

"Sugar" is a term commonly used but challenging to define precisely. In dietary contexts, it typically refers to mono- or disaccharides, often described as simple carbohydrates.

Sugars are a type of carbohydrate, which are organic compounds made of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms. They are classified as simple carbohydrates due to their simple chemical structure. There are various types of sugars, but they can be broadly categorized into monosaccharides and disaccharides.

Monosaccharides: These are the simplest form of sugar and are often referred to as simple sugars. They cannot be hydrolyzed into simpler sugars. Common monosaccharides include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Glucose, in particular, is a primary energy source for living organisms.

Disaccharides: These sugars are formed when two monosaccharides are joined together and a molecule of water is removed - a process known as dehydration synthesis. Common disaccharides include sucrose (table sugar), which is a combination of glucose and fructose; lactose, found in milk, which is made of glucose and galactose; and maltose, formed from two glucose molecules.

How is sugar metabolised in the body?

The metabolism of sugar in the body is a complex process involving several steps and pathways.

The journey starts with digestion and absorption. When you consume foods containing sugars (like sucrose, lactose, or fructose), they are first broken down into simpler sugars (like glucose) in the digestive system. Enzymes like sucrase and lactase in the small intestine help in this breakdown. Once broken down, these simple sugars are absorbed into the bloodstream through the intestinal walls.

The next step is transport to the liver. After absorption, the sugars are transported to the liver. Fructose and galactose are converted into glucose in the liver. This process ensures that the majority of the carbohydrate energy available to the body is in the form of glucose.

After converting carbs to glucose in enters the bloodstream. Glucose in the bloodstream enters body cells with the help of insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. In the cells, glucose undergoes glycolysis, a process that breaks down glucose into pyruvate, releasing energy that the cell can use. This process happens in the cytoplasm of the cell and does not require oxygen (anaerobic process).

Pyruvate from glycolysis is then used in the mitochondria of cells in a process called cellular respiration, which requires oxygen (aerobic process). This process produces ATP (adenosine triphosphate), which is the primary energy molecule used by cells for various functions.

If there is excess glucose in the bloodstream (more than the immediate energy needs of the body), it is stored for future. Insulin plays a key role in this process. Glucose is stored as glycogen in the liver and muscles. When the body needs more energy, glycogen is converted back into glucose. If the glycogen storage capacity is exceeded, the body converts the excess glucose into fat, which is then stored in adipose tissue throughout the body.

So, if sugars are important for generating energy in the body, why are they considered bad?

Sugars are essential for generating energy in the body, but they can be considered harmful when consumed in excess, particularly in the form of added sugars.

Wait, what do you mean by added sugars?

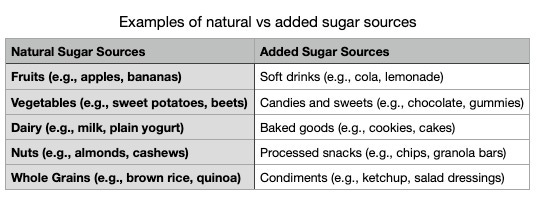

It's important to distinguish between added sugars and naturally occurring sugars found in fruits, vegetables, and dairy products. The latter are part of whole foods that also contain fiber, essential nutrients, and other beneficial compounds. The negative health effects are mostly associated with added sugars, not the sugars naturally present in whole foods.

Why are added sugars considered bad, but naturally occurring sugars are okay?

Excess sugar regardless of the source needs to be avoided and added sugars and naturally occurring sugars are metabolized by the body in similar ways, but their overall impact on health can be quite different due to the context in which they are consumed.

Naturally occurring sugars are found in foods that are often nutrient-dense. For example, fruits contain vitamins, minerals, fiber, and water along with natural sugars. These additional nutrients contribute to a balanced diet and have various health benefits. In contrast, added sugars, such as those in sodas, candies, and baked goods, provide empty calories with little to no nutritional value.

The fiber in whole foods like fruits slows down the digestion and absorption of sugar, leading to a more gradual rise in blood sugar levels. This is beneficial for maintaining stable energy levels and a healthy glycemic response. Added sugars, however, are often in foods with little or no fiber and thus get absorbed quickly, causing rapid spikes in blood sugar and insulin levels.

Diets high in added sugars can displace healthier foods, leading to an overall decrease in nutritional quality. This can contribute to deficiencies in essential nutrients and negatively impact overall health. On the other hand, a diet rich in whole foods with naturally occurring sugars is generally associated with better health outcomes.

Excessive consumption of added sugars has been linked to various health issues, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and dental cavities. These risks are primarily due to the high calorie content and rapid sugar absorption of foods with added sugars, as well as their association with unhealthy dietary patterns.

Ok, so how much sugar is too much?

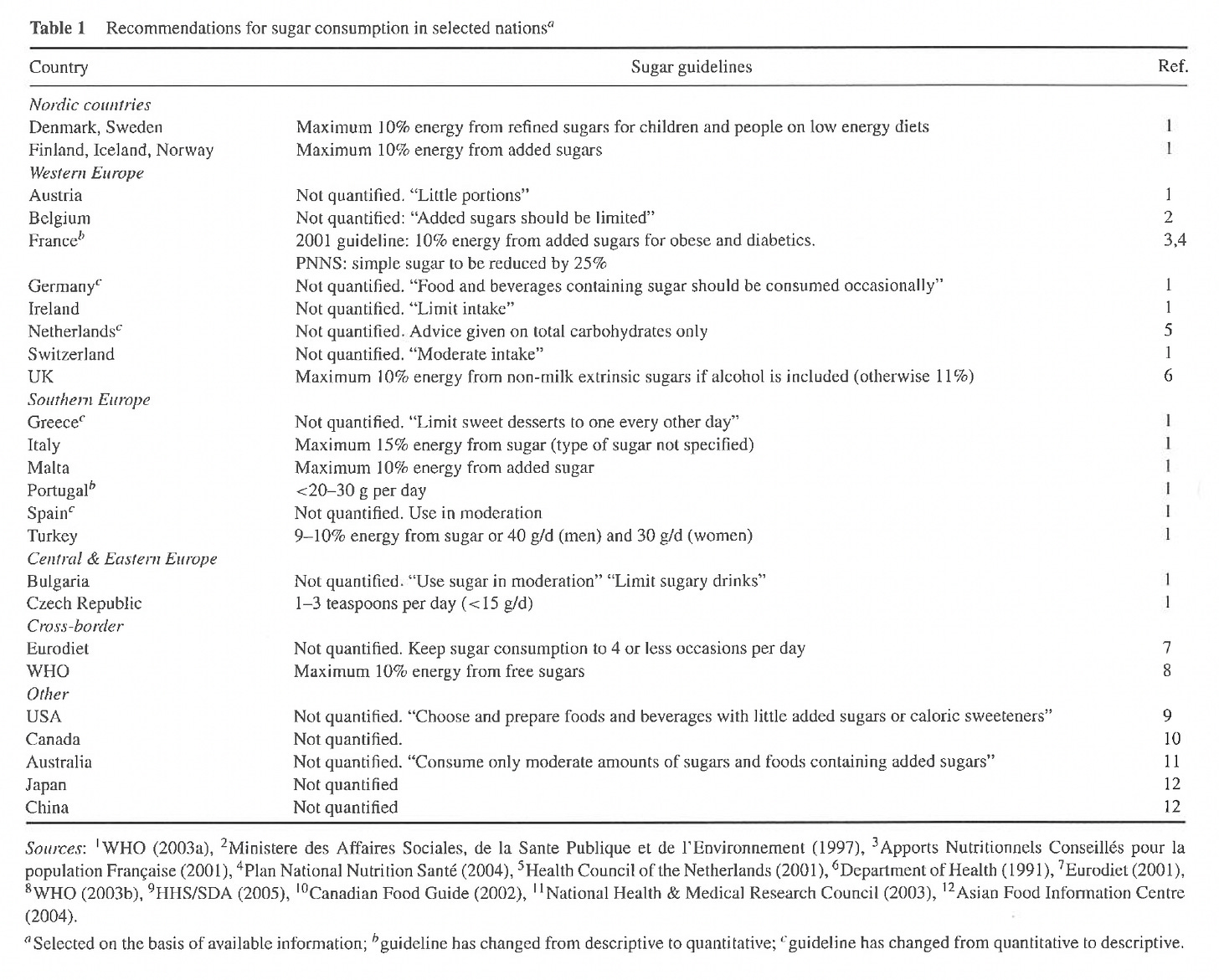

As we can see from the table below, the recommendations for sugar consumption in selected countries did not provide a clear cut-off in most of the cases, based on a publication from 2010.

A recent umbrella review in the BMJ published in 2023 provides compelling insights into the impact of dietary sugar on health. Covering 83 health outcomes from over 8,600 articles, this comprehensive study underscores the detrimental effects of high sugar consumption, particularly in relation to cardiometabolic diseases. Its significance lies in the robust methodology, which includes a thorough analysis of existing meta-analyses, lending credibility and depth to its findings. Importantly, it suggests a significant reduction in free or added sugars to below 25g/day and limiting sugar-sweetened beverages to one drink maximum per week. To put the recommended limit of 25 grams of sugar per day into context, this amount equates to about 6 teaspoons. In comparison, a typical can of sugar-sweetened beverage can contain approximately 39 grams of sugar, which is roughly equivalent to 9 to 10 teaspoons of sugar. This means that just one can of such a beverage would exceed the daily recommended sugar intake by a significant margin, illustrating how easily one can surpass dietary sugar limits through processed foods and drinks.

What are the health risks of high dietary sugar intake?

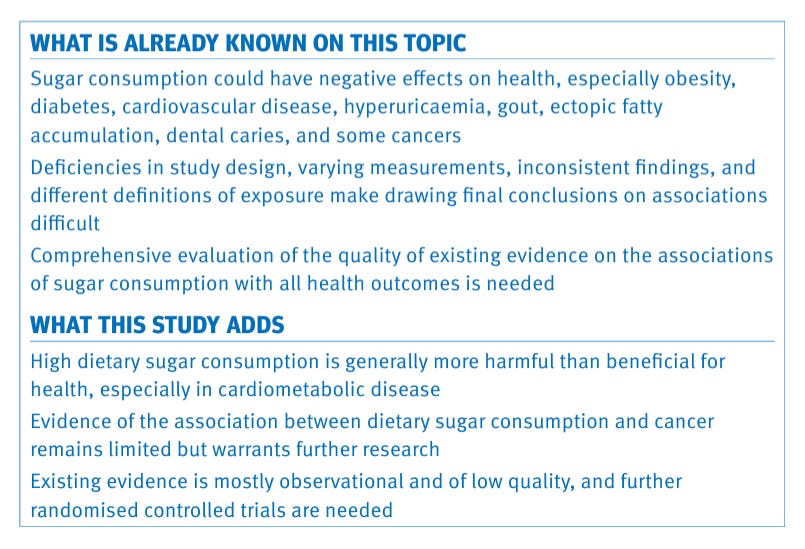

The prevalent understanding is that sugar intake may adversely affect health, including obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers. However, research inconsistencies and differing study designs complicate definitive conclusions about sugar's effects.

Based on the umberlla review in BMJ high sugar consumption is largely detrimental, particularly for cardiometabolic health. The study notes the association between sugar and cancer is not well-established, suggesting a need for higher-quality research, such as randomized controlled trials, to explore this relationship further.

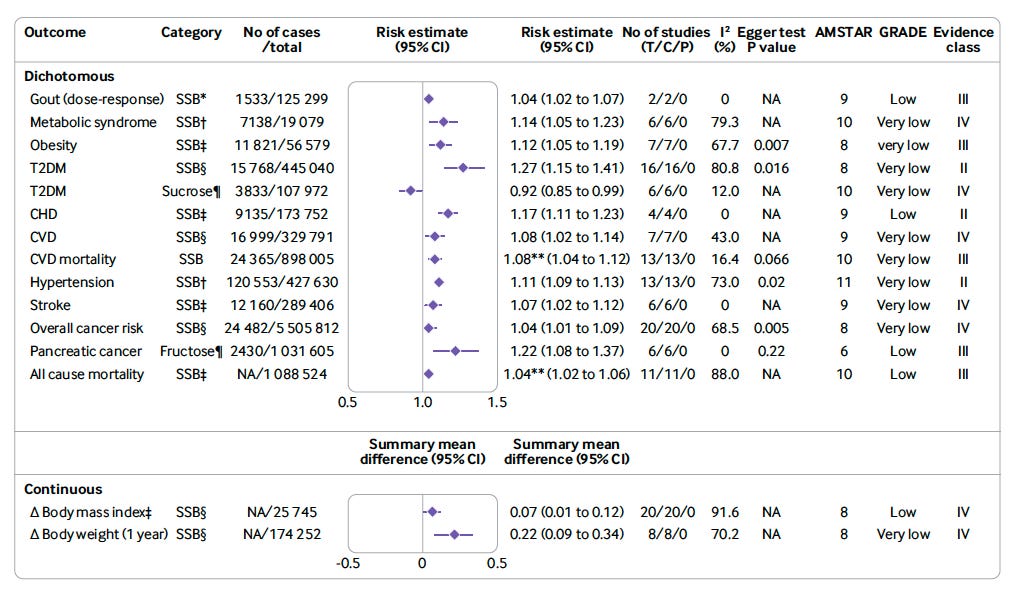

The table above summarizes research on how sugary drinks and sucrose (table sugar) might affect the chances of developing certain health issues. Each health issue listed has a "risk estimate," which is a number that shows how much the risk goes up or down when people consume sugary drinks or sucrose. If this number is above 1, it means there's an increased risk; if it's exactly 1, it means there's no change in risk; and if it's below 1, it means there's a decreased risk.

These risk estimates come with a "95% confidence interval" (CI), which is a range of numbers around the risk estimate. Think of it as a safety net that says, "We're 95% sure the real risk is somewhere inside this net." If the net crosses the number 1, we’re less sure that the risk is real because the "net" includes the possibility of no risk change.

Based on the table, the link between sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) consumption and both obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is present, but the confidence in the data, as reflected by the GRADE evidence class, is "very low" for obesity and "low" to "very low" for T2DM. This suggests that while there appears to be an association, the available studies may have limitations or inconsistencies that make it difficult to draw firm conclusions.

The "very low" and "low" GRADE classifications indicate that the evidence is not strong enough to be conclusive due to potential issues such as small study sizes, methodological flaws, variability in study results, or other factors that could affect the reliability of the findings.

In simple terms, while there is some indication of increased risk of obesity and T2DM with higher sugar intake, particularly from sugary drinks, researchers are not completely certain about this link because the studies they have to work with are not robust enough to eliminate all doubts. More high-quality research is needed to clarify these associations.

What does a link mean? Does it mean that eating more sugar causes obesity and T2DM?

A "link" or "association" in epidemiological terms means there's a statistical relationship between two factors – in this case, sugar consumption and health outcomes like obesity or T2DM. It means that when one factor is present, the other factor is more likely to be present as well, based on the data analyzed.

However, this does not necessarily imply causation. Causation means that one event is the direct result of another; that is, sugar consumption would directly cause obesity or T2DM. Establishing causation in medicine requires demonstrating that the factor (sugar in this case) consistently leads to the outcome (like obesity or T2DM), that it precedes the outcome, and that other explanations for the outcome have been ruled out.

In epidemiological studies, especially observational ones, it can be challenging to prove causation because there may be many other variables at play that could influence the results, known as confounding factors. For example, people who consume high amounts of sugar may also have other lifestyle factors contributing to obesity or T2DM, such as lower physical activity or unhealthy diet patterns in general.

So, in summary, a link indicates a relationship, but not necessarily a direct cause-and-effect scenario. To determine causation, more rigorous research, often including longitudinal studies or randomized controlled trials, is needed to control for other factors and to establish a temporal sequence.

Public health guidelines are often based on the best available evidence at the time, which frequently includes epidemiological data. Even if individual studies don't establish causation definitively, when multiple studies point in the same direction, it suggests a pattern that may inform guidelines. For example, if numerous studies show that higher consumption of sugary drinks is associated with increased rates of obesity and T2DM, it is reasonable to advise moderation in consumption while more definitive research is pursued.

Guidelines are part of risk management strategies. If there is a potential risk to public health, guidelines may be created as a precaution, especially if the intervention (e.g., reducing sugar intake) is low-risk and aligns with broader health recommendations. Plus, guidelines are more likely to be developed when there is a biologically plausible mechanism linking the behavior to the outcome. For sugar, the mechanisms linking it to weight gain and insulin resistance are well understood, lending credence to the epidemiological associations.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the gold standard for establishing causation, are often not ethical or feasible for long-term lifestyle factors. For example, it would be unethical to ask a group of people to consume a high-sugar diet for several years to see if they develop diabetes. Therefore, guidelines must rely on the best available evidence, which often comes from observational studies.

As such, recommendations to limit sugar intake are consistent with broader dietary guidelines that emphasize whole foods and balanced nutrition, which have been associated with better health outcomes. Moreover, If the potential benefits of a guideline (e.g., reduced sugar intake leading to lower obesity rates) are deemed to outweigh any potential harms, and the intervention is a low-risk one (e.g., eating less sugar), then it may be considered justified to issue the guideline.

Public health guidelines are, therefore, often a balance between scientific evidence, practicality, ethical considerations, and risk-benefit analyses. They are usually conservative and aim to provide guidance that will benefit the population overall, while causing minimal harm.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, while sugar is an essential source of energy for the body, moderation in its consumption is vital. It is important to distinguish between naturally occurring sugars, which are accompanied by beneficial nutrients, and added sugars, which provide empty calories and contribute to health risks. Nonetheless, the depiction of sugar as inherently evil, as presented by numerous popular podcasts, is blatantly incorrect, even if the intent is to convey a strong message to the public. As such, awareness and moderation are key, as is advocating for a balanced diet and responsible food choices to safeguard against the potential dangers of high sugar intake.